Journée d’études : Philology and Archaeology

mai 24, 2022 @ 8h00 - mai 25, 2022 @ 17h00

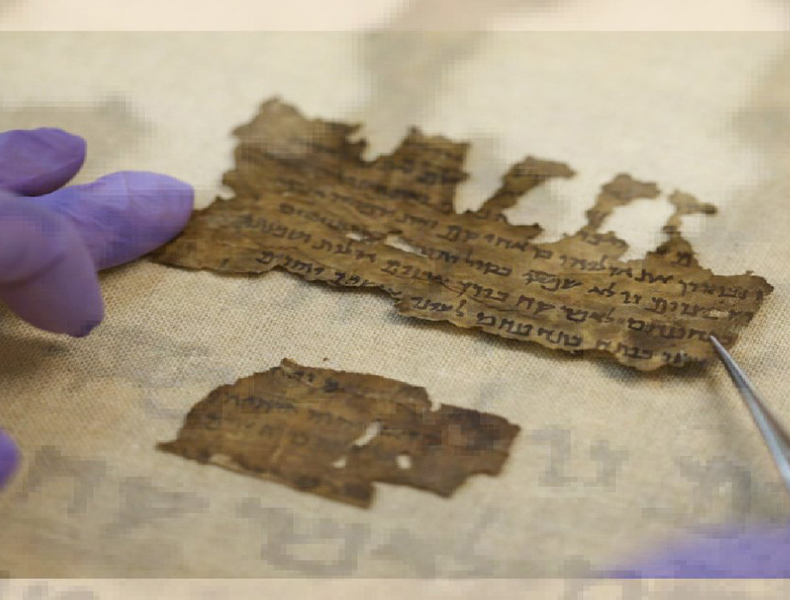

Since the nineteenth-century, there have been numerous examples of eminent findings of manuscript collections in archaeological contexts. Some of these have necessarily captured the attention of philologists, starting with the hundreds of thousands of manuscripts from the genizah of Cairo, unearthed in 1896, which have since produced a refined social history of the medieval city. A few years later, the caves of Dunhuang yielded thousands of manuscripts from multiple traditions, especially Buddhist, allowing a recasting of historical studies on its diffusion along the silk road during the first millennium. Similarly, the manuscripts of Qumran, found from 1947 in clay jars on the edge of the Dead Sea, revolutionised biblical studies, offering direct access to texts hitherto uniquely available at the end of a long chain of transmission. Likewise, the Qur’anic manuscripts discovered at the Great Mosque in Sanʿāʾ and the multi-lingual manuscripts found at the Qubbat al-Khazna at the Umayyad Great Mosque in Damascus have invigorated philological and historical research. Alongside these outstanding discoveries, how many more manuscripts were found through archaeological explorations and away from institutions crafted to preserve them, such as libraries or archives?

These fortuitous manuscript discoveries do not exhaust all the intersections between philology and archaeology, but they stress the need to rethink their relation. Building on case studies of textual corpora uncovered by archaeology, this workshop aims to re-interrogate the common history, and explore a few missed epistemological encounters between the two disciplines.

Whether in biblical studies or classical studies, for instance, archaeology and philology share common topics and periods of the past that specialists can grasp, either through texts that have been transmitted by the traditions of preservation and copying, or through the material assemblages that have been uncovered by archaeologists. Archaeology and philology also share a common discipline – epigraphy – which mobilises material and textual registers in various ways.

Nevertheless, the history of epigraphy illustrates the chronological gap between the institutionalisation of philology and that of archaeology. In the Western tradition, nearly three centuries separate their recognition as fields of knowledge of the past. In Europe, academies of inscriptions go back to the 16th century, in the wake of the scientific triumph of philology, while archaeology had to wait until the 19th and even the 20th century to be endowed with scientific institutions. Even though complementary, their respective histories consist of gaps, of competition, of dominant and auxiliary positions, of the wish for autonomy and independence.

Although philology and archaeology regularly intersect over topics, periods, and even disciplines such as epigraphy, they continue to be suspicious of one another, ready to declare themselves epistemologically irreconcilable. For instance, the notion of context, rather than representing a common heuristic vocabulary, often divides the two knowledge systems. While philology’s ideal has long appeared as the establishment of an original text capable of definitively freeing itself from all that it does not contain, and from the different contexts that it has passed through or that have passed through it, the practice of archaeology gives context a unique place in knowledge production when the objects unearthed have meaning only through their exact situation and localization, and through their link to the external context.

One also finds many similarities from the point of view of techniques of knowledge. Stemmatology on the one hand, stratigraphy on the other; both seek an original item and meaning, recalling the similarities of the two approaches. Their complementarity is rarely examined besides a clear ‘chiasmatic’ relation. Philology aims towards materialising meaning; archaeology towards semanticising materiality. In recent years, the developments in textual studies, such as material bibliography, have clearly confirmed the possibility of a convergence. Manuscripts found in an archaeological context highlight particularly well the need for a material science of textual supports.

Possible topics for contributions include, but are not limited to:

- Case studies of manuscripts unearthed by archaeology

- History of philological and archaeological scholarship

- Archaeology at the service of philology & philology at the service of archaeology

- Comparative epistemological studies of philology and archaeology

- Historical accounts of the uses of context in archaeological and philological research

- History of manuscript transmission over time (traditions and institutions)

- The politics of contextualisation and territorialisation in colonial and nationalist knowledge production (“facts on the ground”)